At first glance, reading an eye prescription can seem confusing because it will have a few different abbreviations that you probably won’t recognize. Once you know what everything means, it will make a whole lot more sense, and you’ll be reading your eye, glasses, and contacts prescription with no problem.

Glasses prescriptions will be broken down by right eye and left eye. The right eye is also referred to as “OD,” and the left eye is “OS”. These abbreviations are Latin for oculus dextrus, meaning right eye, and oculus sinister, meaning left eye.

Most eyeglass prescriptions consist of 3 main parts – the sphere (SPH), the cylinder (CYL), and the axis. The sphere component will be the first number you see on a written glasses prescription. This will tell what type and how much nearsightedness (myopia) or farsightedness (hyperopia) a patient has. Related: find the best places to buy eyeglasses online.

Nearsighted/myopic patients will have a minus (-) at the front of the sphere component. Farsighted/hyperopic patients will have a plus (+) at the front of the sphere component.

The next two parts of the prescription, the cylinder and the axis, provide information regarding how much and what type of astigmatism a patient has. Astigmatism is a condition in which the eye is shaped more like a football rather than like a perfect sphere like a soccer ball. This causes light to focus on two separate locations on the back of the eye, resulting in blurry or smeared vision.

The cylinder and axis part of the prescription allow light to be focused back onto one spot of the back of the eye, resulting in clearer vision. The cylinder, the cyl, of the prescription is the amount of astigmatism correction, and the axis is the location of the astigmatism.

Patients past the age of 40 might also have an ADD power written on their prescription. The ADD helps correct presbyopia, a condition of the normal aging process in which patients are not able to see up close as easily. The ADD power allows patients to see better up close and will range anywhere from +0.75 to +3.00.

What do all of those eye prescription abbreviations mean? (ADD, Axis, BO, BI, diopters, etc.)

ADD – The ADD refers to the add power of the bifocal or multifocal part of a prescription. This helps patients past the age of 40 who are presbyopic see clearly up close.

Axis – Refers to the location of the astigmatism correction in a pair of glasses or contacts. An axis can range from 0 to 180. Most axes will be around the 180 or 90 area.

Related: best contacts for astigmatism

BO – Refers to Base Out prism. Prism can be incorporated into glasses for patients who have binocular vision issues or who might see double. Most glasses will not have any prism incorporated into the lenses unless otherwise specified by your doctor.

BI – Refers to Base In prism. Prism can be incorporated into glasses for patients who have binocular vision issues or who might see double. Most glasses will not have any prism incorporated into the lenses unless otherwise specified by your doctor.

Diopters – A diopter is the standard unit of measurement for glasses and contact lens prescriptions. A diopter is equivalent to one whole numerical value. So if a patient has -0.50 amount of prescription, this can also be referred to as half a diopter.

What do the numbers mean in your eye prescription?

The numbers in a glasses prescription are a way to quantify how much power is needed in order to correct your refractive error. Refractive error is a very common condition in which the eye is misshapen, causing light entering the eye to not focus properly resulting in a blurry image. The prescription put into glasses and contacts allows the light to be refocused so that a clear image is formed and you will see clearly.

The numbers are just a way to tell how much prescription is needed in order for you to see clearly. Glasses and contact lens prescriptions increase in increments of quarters (0.25 steps) of diopters.

Examples of Different Glasses and Contact Lens Prescriptions

Example of a nearsighted glasses prescription:

Nearsighted, or myopia prescriptions, will have a minus (-) sign in front of the prescription. Note that with a prescription that ONLY has a nearsighted component and no astigmatism, the “SPH” label will be put behind it. This just signifies that the prescription only has a spherical component, and no astigmatism or “cyl” value.

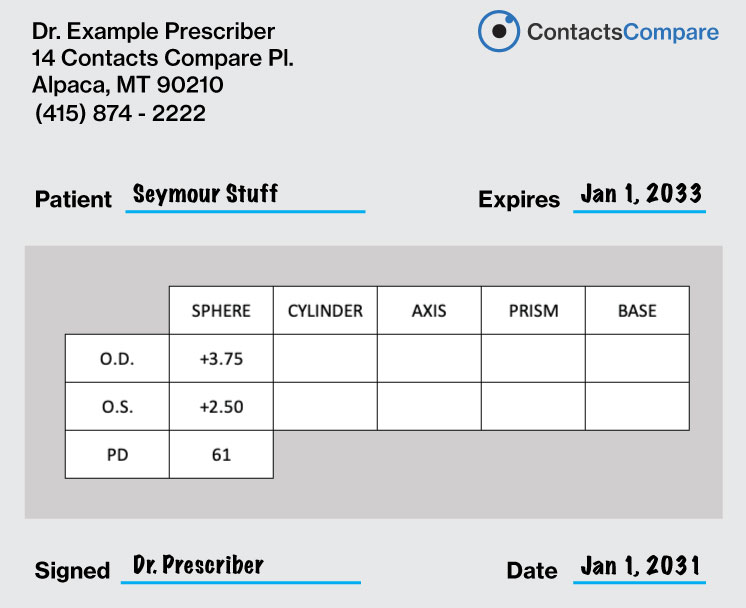

Example of a farsighted glasses prescription:

Farsighted, or hyperopic prescriptions, will have a plus (+) sign in front of the prescription. Note that with a prescription that ONLY has a farsighted component and no astigmatism, the “SPH” label will be put behind it. This just signifies that the prescription only has a spherical component, and no astigmatism or “cyl” value.

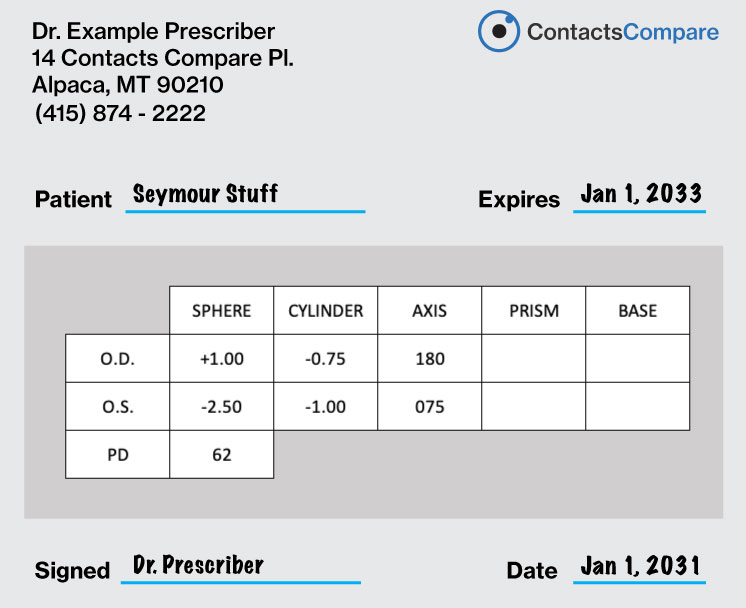

Example of an astigmatism glasses prescription:

Note that astigmatism prescriptions will have 3 sets of numbers, the spherical component at the front, the cylinder component in the middle, and the axis at the end. The last two components of the prescription bolded above, the cylinder and the axis, correlate to the amount and the position of the astigmatism. The front part, the spherical component, tells whether the patient is nearsighted or farsighted.

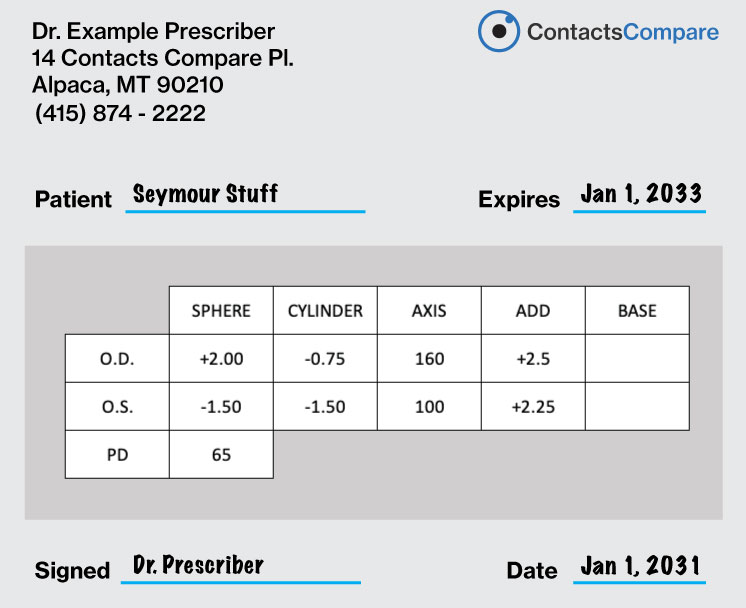

Example of a glasses prescription for presbyopia:

The big difference you’ll see here is that a value is included for ADD. As you might remember, ADD stands for Addition. It tells the glass manufacturer or distributor the additional correction required for you to read things up close. Because presbyopia results from the lens no longer being able to flex and focus on things at varying distances with age, it’s used in bifocal and reading glasses. In other words, ADD represents the extra power over the distance prescription that is already included.

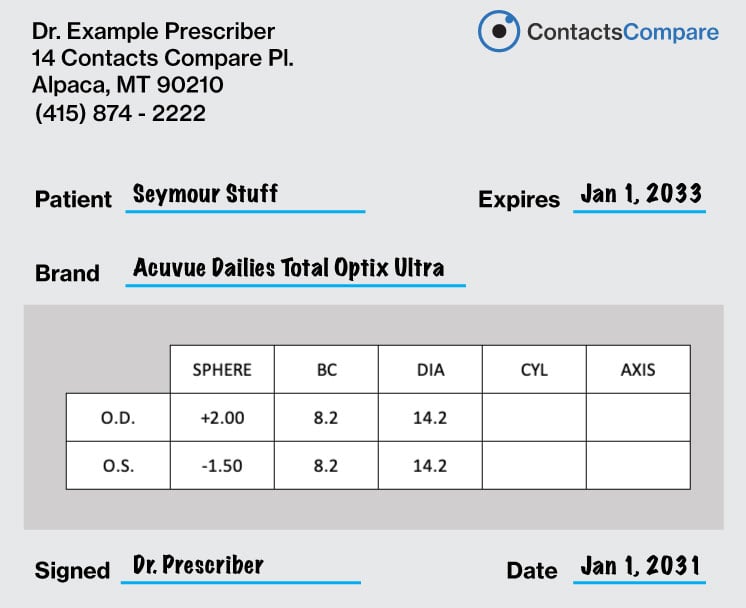

Example of a contact lens prescription:

Note that contact lens prescriptions will include more information including the lens brand, diameter of the lens, and base curve (also known as the curvature) of the lens. All of these different factors are taken into account when an eye doctor fits a patient for the correct contact lens.

How do eye doctors determine your vision prescription (step by step explanation)

Most people think that determining a glasses prescription is an easy process that consists of a simple, “Which is better, 1 or 2?” However, determining a patient’s prescription is a very complex process that has many steps.

The first thing the doctor will do that helps determine a patient’s prescription is actually just talking to the patient about their ocular history and visual complaints and needs. A patient’s visual symptoms will actually tell a lot about their prescription, and it is important to know what a patient is doing with their eyes all day as this will determine what the doctor will prescribe.

For example, it is very important to know if a patient is a truck driver who requires very sharp distance vision, versus a patient who is an accountant who is on their computer most of the day. Both of these patients might end up having the same prescription, but the doctor will tweak the prescription and suggest different lens styles based on the patient’s complaints and needs.

The next step in the prescription process is obtaining an estimate of the prescription. Most practices will have an autorefractor machine that takes a scan of the eye and finds a rough estimate of what the prescription might be. Another way to get an estimate of the prescription is through a skill called retinoscopy, in which the doctor will shine light into the patient’s eye and use different lenses in front of the eye to find the estimated Rx.

After this estimated prescription is obtained, the doctor will put that prescription into a machine called a phoropter. The phoropter is the classic piece of equipment that you see in TV shows and movies in which the doctor will do the whole “1 or 2” bit.

The secret sauce is in the refraction

A refraction is done with the phoropter in which the doctor will show the patient different lens options and compare them back and forth to find which lenses are clearest for the patient. The refraction ends with the set of lenses that gives the patient the best, clearest vision – aka the prescription!

Depending on the patient’s complaints, the doctor may decide to tweak the prescription from the refraction. Oftentimes what the doctor will prescribe will be a little different from what the last set of lenses in the phoropter were. There truly is an art to prescribing and this whole process is much more complicated than a simple set of questions.

Is there a way to translate a glasses prescription into a contact lens prescription?

Kind of but it’s not a simple or standard translation. Glasses and contact lens prescriptions contain separate numbers and information so they cannot easily be translated. In fact, a separate prescription is required for both.

A contact lens prescription will contain additional information including the lens brand, the diameter of the lens, and the base curve of the lens.

The actual numbers between glasses and contact lens prescriptions can also differ. Depending on how high the glasses prescription is, the contact lens prescription will either be stronger or weaker depending on what type of refractive error the patient has (either nearsighted or farsighted).

Astigmatism contact lenses, also known as toric lenses, are also not made in every prescription power and axis. Your doctor will have to closely evaluate the glasses prescription in order to compute the correct contact lenses prescription.

How often should you get an eye exam?

You should see an eye doctor for an eye exam annually. Most glasses and contact lenses prescriptions expire after 1 year so you will need an annual eye exam to renew the prescription. It is also important to schedule a yearly eye exam to rule out any concerning ocular health conditions like dry eye, cataracts, glaucoma, macular degeneration, and more.

Why do eye prescriptions expire?

Prescriptions expire because your eyes will change over time. This causes your old prescription to be inaccurate. An old prescription that is too strong or too weak can cause symptoms like eyestrain, headache, blurred vision, trouble focusing, etc. An accurate up-to-date glasses or contact lens prescription will ensure that none of these issues are related to uncorrected refractive error/prescription.

Contact lens prescriptions also need to expire yearly (or every two years in some states) so patients will have their ocular health checked each year. Since contact lenses are considered medical devices that are directly touching the front surface of your eye, there is an increased risk for infection, disease, or contact lens-induced corneal hypoxia. Corneal hypoxia occurs when the front surface of the eye, the cornea, is not receiving enough oxygen. This can result in new blood vessel growth on the cornea, corneal swelling, and blurred vision.

These are very serious ocular health concerns that can lead to very serious, irreversible damage so that is why it is important that the contact lenses are evaluated yearly.

Is it normal for my prescription to change annually?

Yes – it is normal for a glasses prescription to change a little bit from year to year. Large changes in prescription are abnormal however and could be a sign of other ocular disease issues occurring with the health of your eyes. It is important to get your prescription and eye health checked annually by an eye doctor so any concerning health issues with the eye can be found and addressed.

Do I have to buy my eyeglasses or contact lenses from my prescriber’s office?

No, by law, your doctor must give you a written copy of your eye prescription after your eye exam so that you can shop around for the lowest prices. A lot of people do purchase their lenses or glasses from their eye doctor or optician for many reasons. But if you’d like to shop around for the lowest prices, our site has a price comparison page which makes it uber easy to quickly see where you can get your contacts for cheap!

Dr. Olivia Burger, O.D. is an optometrist who graduated from the Pennsylvania College of Optometry. She is pursuing a 1-year residency at the UC Berkeley School of Optometry in Vision Science in Primary Care / Contact Lens. Her optometric areas of interest include private practice, contact lenses, and optometric service organizations such as VOSH. In her free time, she enjoys live music and is a freelance concert photographer.